Variance reports measure units used against units sold and are mainly used by bar operators to minimize inventory variances. Variances can be “up” (an overage) or “down” (a shortage).

Being “up” means the bar used less inventory than theoretically necessary. Being “down” inventory is what most operators fear – and for good reason. Almost every bar owner has worked at a bar in their past where theft was rampant, so most bar owners know that it’s not just a small amount of inventory that can go missing. It can literally be thousands a night, and even hundreds of thousands a year that a bar can be missing if a combination of no inventory control + bad staff + a bad owner all come together.

Successful bar operators avoid this problem by doing weekly counts and running variance reports to keep everything in line. But even though most people have heard of and seen variance reports, not everyone sees and uses variance reports the same way.

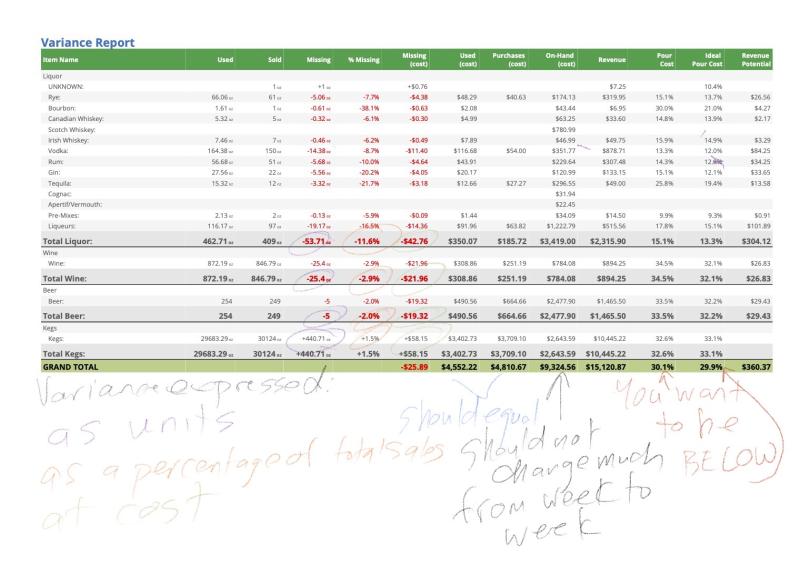

I have spent close to two decades doing reports like these for bar operators and have seen the responses from both unsuccessful and successful operators. In the right hands, variance reports can save a bar operator tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. Looking at the variance report in the example below, I am going to review five observations I have seen and how high level operators interpret and use the data.

1.) Thinking of Weekly Variances in 52 Week Increments

Looking at the example report, we see that the bar is Missing -53.71 oz on period. That represented an 11.6 percent shrinkage rate at a cost of $42.76 to the bar. If that inventory was sold at retail, it could have been sold at $304.12 (which is on the far right under the revenue potential column). While $42.76 at cost and $304.12 at retail sounds small for one week, when you multiply this effect over the course of 52 weeks, it works out to 2756 ounces worth $2223.52 at cost, and $15814.24 at retail. And that’s “just” the liquor category. If you look at the other categories, you’ll see that there are also shortages in wine and bottled beer as well, each with corresponding costs and retail value. While this may seem extreme, wise operators see weekly variances in 52 week increments to see the potential impact of not correcting mistakes today.

2.) Used (Cost) vs. Purchases (Cost)

Wise operators watch what their bars USE, what they BUY and what they HAVE. In the example report, the bar used $4552.22 in inventory, and purchased $4810.67 during the same period. So, he purchased around $300 more than he used in the previous week. In a perfect world you want these numbers to be close. So, this guy didn’t do too bad in this area for this audit period. However, if Used (cost) is significantly MORE than Purchases (cost), that’s an indication that the bar could be understocked and may encounter supply issues. If purchased (cost) is significantly MORE than used (cost) than this could lead to an overstock and therefore an inefficient use of capital.

Your On-Hand (cost) represents the monetary value of the inventory. You keep your On Hand (cost) number at its optimal level by keeping your purchases as close as you can to what you use in the previous week. This is most easily accomplished by ordering based on pars, which keep the bar fully stocked but always within budget. Whenever you see bars that have their On Hand (cost) numbers go up and down over the year, that’s usually an indication that whoever is doing the ordering is not using set pars. It would surprise you how many managers eyeball inventory counts and eyeball purchases with no real set method to determine order amounts, and some bars have thousands of dollars over invested in inventory that would be much better utilized elsewhere. Wise operators watch these numbers to always ensure an efficient use of capital.

3.) Pour Cost vs. Ideal Pour Cost (This Is Also Known as Actual COGS vs. Theoretical COGS)

Pour Cost is how much the bar used in product to make its sales expressed as a percentage. You measure that number against the Ideal Pour Cost, which is how much each item that was rang into the POS costed when expressed as a percentage. This can only be measured by comparing an itemized usage report against an itemized sales report so you can see exactly what left the building, and then compare it to exactly what was sold. This is the reason why I discourage any kind of inventory procedure that involves weighing all bottles together as a category – and also why I also discourage any kind of POS set up where common buttons like “Highball” can be pressed, and several different products poured. With vague counting procedures and vague POS procedures, you don’t really have a true picture of what is actually being used or sold each week.

Ideally you want your Pour Cost to be BELOW your Ideal Pour Cost. In this case, this bars pour cost is 30.1 percent and his ideal is 29.9 percent, which means he is 0.2 percent above his theoretical. Not bad, but definitely has room to improve. In my ideal world, this guy would be running at a 29 percent pour cost and be below his ideal pour cost of 29.9 percent. The next section will detail how to be below your ideal pour cost.

4.) Understanding The Reality of Pouring Perfect Ounces

Liquid that is poured by hand will never be done perfectly. When you measure liquor on a digital scale, even the best bartenders will be off by 0.01 or 0.03 of an ounce every time they attempt to pour 1 ounce. That’s just how free pouring liquid works. This harsh reality of free pouring leaves operators with two choices. They can either be “up” on ounces, or “down” on ounces. I strongly encourage operators to choose to be “up” on ounces by “slightly” short pouring every drink to stay under the theoretical pour size. But before you get all uppity on me, let me explain what I mean.

While losing on every pour while trying to give the customer “a perfect ounce” SOUNDS like a good idea, it really is not. If you attempt to pour a full ounce into a shot glass to the brim of the glass, you will likely go over by 0.02 - 0.05 oz because the meniscus that forms at the top of the shot glass is a subjective measurement. If that “perfect ounce” with a meniscus is in a shot glass, I guarantee you that by the time the server brings the shot to the table, anywhere from 0.05 to 0.1 of the “perfect ounce” has gone over the edge of the glass and is on the serving tray. If that same shot were served directly to the guest, that same 0.05 to 0.1 oz would go over the edge of the shot glass once tilted and will be on the guests fingers.

Back when I bartended in night clubs, part of my routine after serving people shots was always handing out napkins. And people always used them. Why? Because people ALWAYS spill that little bit of booze on their fingers when the glass is tilted. Neither the guest, the bartender or the bar owner receive any benefit from pouring like this.

If you consistently pour 0.95 to 0.97 of an ounce on each pour, you will stay below your theoretical and your guests will not perceive the difference due to the factors I listed above. I am not talking about ripping customers off by pouring 0.7 oz and 0.8 oz, which you can noticeably see in a shot glass. I am talking about staying beneath the meniscus on every pour and making a conscious effort to never exceed the capacity of the portion control tool. This is actually the reason why whenever you order a 20 oz pint of beer, you’re really not actually getting 20 oz of beer. You’re getting a glass with something close to 20 oz, depending on how much head they leave at the top of the pint. Several pint glasses across the industry measure out at exactly 20 oz to the brim of the glass, therefore it is impossible to put more than 20 oz of liquid into these glasses. If 20 oz exactly is poured into that glass, it will be so full it either ends up on the tray or on the guests fingers. That’s actually what pouring a “perfect” ounce will get you in the real world.

Looking at the example report, you will see that the one category this bar is “up” on is kegs. The bar is +440 oz on 30124 oz rang into the POS. That represents a 1.5 percent overage, which means that if he serves 20 oz pints, 19.7 oz goes into each one. That is a pretty full pint glass my friends, and I doubt any customers are sending pints back to the bartender requesting new beers because 0.3 oz is not in the glass. That +440 oz the bar saved by slightly short pouring resulted in the bar retaining $58.15 at cost. Over the course of 52 weeks that’s worth $3023.80 at cost. I don’t know about you, but I’d rather have that $3023.80 in my bank account rather than seeing it go down the drain, wiped off a serving tray or on a guests fingers. This is why wise operators choose to be “up” on ounces.

5.) Examining Variances as Percentages and What They Mean

Looking at your variances in ounces means very little without looking at how those ounces compare to the total amount of ounces that were served for that item. While being short 100 ounces of liquor sounds horrible, if 10000 ounces were served on that audit period, that’s only a one-percent when expressed as a percentage. Percentages offer clues as to why variances are happening.

Shortages ranging from one to five percent can usually be traced to bar teams unconsciously over pouring because they have not gotten the pep talk about trying to pour perfect ounces like I mentioned in the previous point. This could also be from incorrect portion control sized tools, like if a cocktail jigger is bigger than a standard ounce. (Be careful you international operators, as metric ounces are slightly different than imperial ounces). But if all the portion control tools are correctly measured out, variances in the one to five percent range are easily corrected by showing the bar team their variance reports and instructing them to take a bit off their pours. These are what I call “heavy hands” and are simple to correct.

Shortages above five percent are a huge problem and need to be addressed immediately with staff. That’s usually a combination of theft, drinking on shift and over pouring. If after being addressed, the shortages still persist at five percent or above, it is usually an issue of a lack of respect by the staff towards the owner. The owner may be too nice in their management style to be effective, or the staff may simply be toxic and need to be terminated.

Big variances like in the 10 to 20 percent range, should have an explanation, like if product was removed and not accounted for, or if a non-delivery for an item on liquor order occurred, or there was a counting error. However, if big variances cannot be traced to legitimate sources, a bar that has variances at this level won’t survive if they remain like that consistently. This is why wise operators watch their percentages and work hard to keep them within an acceptable threshold.

Kevin Tam is a Sculpture Hospitality franchisee with more than a decade of experience working directly with bar, restaurant and nightclub owners on all points of the spectrum. From family-owned single bar operations to large companies with locations on an international scale, Tam works with them all and understands the unique challenges each kind of company faces. He’s also the author of a book titled Night Club Marketing Systems – How to Get Customers for Your Bar. He is also a regular writer for Bar Business Magazine, Bar & Restaurant, and publisher of an eBook called: The 5 Commonly Overlooked Areas That Kill Your Food Cost.

Plan to Attend or Participate in

Bar & Restaurant Expo, March 27-29, 2023

To learn about the latest trends, issues and hot topics, and to experience and taste the best products within the bar, restaurant and hospitality industry, plan to attend Bar & Restaurant Expo, March 27-29, 2023 in Las Vegas. Visit BarandRestaurantExpo.com.

To book your sponsorship or exhibit space at Bar & Restaurant Expo, contact:

Veronica Gonnello

(for companies A to G)

e: [email protected]

p: 212-895-8244

Tim Schultz

(for companies H to Q)

e: [email protected]

p: (917) 258-8589

Fadi Alsayegh

(for companies R to Z)

e: [email protected]

p: 917-258-5174

Also, be sure to follow Bar & Restaurant on Facebook and Instagram for all the latest industry news and trends.