Club and Bar Operators Flex their Economic Muscle and Collaborate with the Community

When was the last time you heard a positive media mention about a city’s nightlife district? Most function well but are ignored until something bad happens, and then the media takes an “if it bleeds, it leads” approach that sensationalizes violence and crime. This paints everyone who runs a business in the nightlife district as part of the problem, though nearly every venue is safe and well run.

Nightlife has a public relations problem. As Jim Peters of the Responsible Hospitality Institute (RHI) in Santa Cruz, Calif., explains, “A lot of people look at nightlife in a negative way because they construe it as a bunch of young people going out to create havoc.”

But nightlife is a significant contributor to a city’s economy and culture. In metros such as San Francisco, Seattle and New York, club operators are leveraging their collective economic power to forge new collaborations involving regulators, nightclubs and neighbors. The result? They’re addressing public concerns while emphasizing the value of the nightlife economy.

The Other Nine to Five

Here’s a curious paradox: a hip urban neighborhood draws new residents for its walkability, fun restaurants and bustling nightlife, but then those same residents sour on nighttime noise and occasional violence. They grow irate and complain to the authorities. Club owners find themselves visited by the police and Alcoholic Beverage Control.

Ariel Palitz, the owner of Sutra in New York City, casts a sympathetic eye toward those neighbors. “Some people say, ‘You knew what you were signing up for.’ But you can’t always use that justification. People have the right to silence and a quality of life.”

Peters and RHI are leading the effort to change the image of nightlife as nothing but trouble. For three decades, Peters has worked with entertainment districts to help manage what he calls their “nighttime” economies. RHI supports 30 cities in the U.S. and Canada.

Peters begins with a demographic lesson: It’s important to understand neighbors and what they value most. He lays out four key demographic groups that cities should consider when creating hospitality zones:

Singles. Young unattached adults, often in their 20s, who go out to meet people. They want venues in which they can dance and people watch, and they mask their insecurities through alcohol. Definitely an after-10-p.m. crowd.

Mingles. People in their 30s or 40s who like music that is good but not too loud; they are there to socialize. Lounges often appeal to members of this group, who tend to have more disposable income.

Families. Their lives are oriented around raising children. If they go out it will be in the early evening, and they probably won’t stay long; babysitters are expensive.

Jingles (from the jingle of money in their pockets). Also known as empty nesters, these are older adults who’ve downsized by moving into the city. They have zero tolerance for late-night street or club noise: they’re home before 10 p.m.

The problem is that the economic contribution of nightlife hasn’t been well stated, other than in the New York Nightlife Association’s report “The $9 Billion Economic Impact of the Nightlife Industry on New York City,” (see “The City That Never Sleeps”). Thus, its positive economic effect is easy to overlook — especially by people who don’t participate in nightlife. Peters stresses that cities should rebrand entertainment districts, which the public often considers solely nightclubs and bars, into hospitality zones that emphasize social activity. “The more you can shift the activity away from drinking establishments to social establishments, you can neutralize some of the resistance to more dining and entertainment venues,” he says.

When working with a city, RHI leads a late-night tour for policymakers to see what happens at closing time, and then evaluates how well they’re doing. “The role of the community is to make these districts safe for people of different generations,” Peters explains. “These can be vibrant areas where they can enjoy themselves.”

Here’s a look at how nightlife, government and community groups are coming to the table in three cities.

San Francisco Listens

San Francisco is the only U.S. city that has an Entertainment Commission, created in 2003. Its charter is to regulate nightlife without impinging on neighbors, thus creating a healthy balance between the two. The city is unique: It is geographically small (only 49 square miles) but densely populated. There is no entertainment district in which to concentrate nightclubs. In fact, every part of the city has a large residential component.

“Our nightlife economy is really important to San Francisco,” says Jocelyn Kane, the commission’s deputy director. The city is a destination — people drive in from around the Bay Area to party, which is good for the city’s economy, she explains.

But with so many people in such a small area, there is frequent intergenerational conflict in neighborhoods with buzzing nightlife, like the Mission District, Kane says. “Our biggest issues are noise and noise,” she quips. With innovations in technology, many clubs employ extensive soundproofing to keep music contained within four walls, but noise is still a problem when patrons go outside to smoke or when partiers sometimes challenge the authorities.

People complain to the commission every day, Kane says, and so she must call each reported venue. “I say, ‘Can we figure out what’s changed and how we can fix it?’” The commission brings neighbors and nightclub operators together directly to mediate, leaving out the police and ABC. “It’s not about punishing people — it’s about fixing the problem. We run on the principle of being a good neighbor.

“Good mediation pisses everyone off because they don’t completely get their way,” Kane concludes. And maybe that’s good, because in a real community, everyone has to compromise in order to live together.

The City That Never Sleeps

Long known as the city that defines American nightlife, New York has experienced an increase in residential development that may undermine that claim to fame. “We’re a few steps behind in the preservation of our own nighttime culture. We have to act really fast to turn the tide and make some common sense out of it,” says Rob Bookman, the counsel to the New York Nightlife Association, of rising tensions between city residents and nightlife operators. “It’s getting too personal between people.”

Six years ago, NYNA conducted an economic impact study that measured New York nightlife’s economic impact at more than $9 billion with 65 million admissions per year — more than Broadway, museums and sporting events combined. “We dwarf that, but as usual, nightlife is ignored,” Bookman complains. “The best thing we can show is that we’re good business operators, not fly by night.”

The organization has worked to improve relations with local government. NYNA is a savvy lobbyist, reminding politicians of the jobs and economic opportunities nightlife creates. It ensures city hall doesn’t just rubberstamp community boards, and it collaboratively produces a Best Practices guide with the city’s police department.

NYNA also is activating the owners and employees of nightlife venues through the New York Nightlife Preservation Community, which formed last summer. The group communicates to “Preservationists” about pro- and anti-nightlife politicians, candidates and legislation, prompting those involved in the industry to get involved in the process.

Sutra’s Palitz is a member of the East Village community board. She sits on the front line between nightlife and neighborhood as a mediator. “Half of the audience members are bar owners, and the other half hate them,” Palitz jokes. “I have to mediate with them all.”

Preserving nightlife is something dear to Palitz, but striking a balance between the two opposing groups is difficult.

“It’s a delicate situation to preserve nightlife and a nighttime economy. People are so aggressive and naïve in their positions. ‘No more nightclubs! Too many nightclubs! Shut them down!’ Or, ‘This is New York — if you can’t take it, get out!’”

Palitz listens to specific community concerns, and after all is said and done, they reach a solution nine times out of 10, she says. ”People still have to live with each other. We want to reach to some mediated conclusion,” Palitz says. “The tensions are very, very high; it’s mixed use, it’s residential, it’s commercial.”

Like Bookman, Palitz would like New York to develop a single, neutral office to deal with nighttime economy issues. “A lot more respect and appreciation needs to be afforded to us so we can preserve the good name of our bad city,” she says. “A little bad is good.”

Nighttime in Seattle

Several years ago, Seattle introduced new club regulations without community input. “It created a horrible tension between businesses and the city,” says James Keblas, director of Seattle’s Office of Film and Music, which supports entertainment development in the city, including nightlife venues. “Three years ago, if you asked me about this, I’d say we don’t have a solution. But since this mess, we’ve decided new regulatory systems aren’t for Seattle. We work with clubs with the assumption that they want to do good and they are positive contributors to the city.”

Seattle’s first option was to crack down on nightclubs, but now the city has developed a policy of assistance first and enforcement second. The city has taken steps in helping club owners navigate the regulatory process, creating a Nightlife Handbook posted to the city’s web site (www.seattle.gov/filmandmusic, click on Nightlife Technical Assistance). This includes every regulatory requirement to open a club or hold an event. Keblas’ office also hired a nightclub liaison to assist with events.

Additionally, the city of Seattle addresses issues before they become problems. Its enforcement team meets monthly to tackle complaints and takes what Keblas calls a surgical approach. “Everything isn’t a nail that needs a hammer,” he explains. “The result of that is we’ve built a really good relationship between the clubs and the city, and we’re a cultural destination for young people.”

To help maintain its cultural status and popularity, Seattle has taken a creative approach to promote responsible club behavior: The city will grant exemption from its 5 percent admissions tax for clubs that operate under certain conditions, such as hiring more live musicians. “This is a business incentive to create the kind of atmosphere we want in our neighborhoods,” Keblas says.

Nightlife has even become an election issue in Seattle, with nightclubs rallying against the incumbent city attorney because of a propensity toward heavy-handed enforcement. The nightclub issue was at the forefront of this race; Pete Holmes, the challenger candidate backed by bar and nightclub owners in the community, won by a landslide. Other mayoral candidates stepped up to reinforce how the nighttime economy contributes to Seattle’s success.

It’s dependent on nightlife to demonstrate the value that it brings to a city, both to the economy and to the culture. “The more we can get people to think outside of just drinking, the better off we’ll all be because it’s more likely you can appeal to a broader range of potential customers,” RHI’s Peters concludes.

Community cooperation can be a positive experience that allows for a healthy nightlife economy. And these days, clubs, bars and restaurants and the municipalities where they operate need to collaborate for the common good. NCB

Points to Ponder

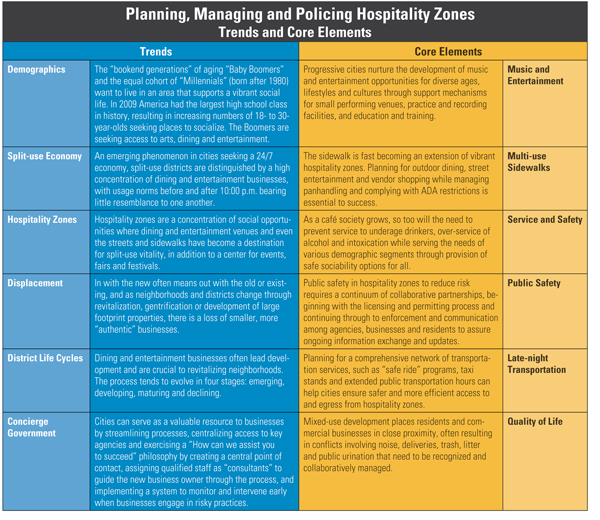

RHI lays out six core trends and elements to consider when developing a hospitality district.

Resources

The San Francisco Entertainment Commission has several public documents posted to its web site, including a Good Neighbor Policy and Principles of Mediation. Read them at

www.sfgov.org/entertainment, under Documents.

Check out the New York Nightlife Association’s report, “The $9 Billion Economic Impact of the Nightlife Industry on New York City,” at www.nysra.org/associations/2487/files/EconomicStudy.pdf, and “Best Practices for Nightlife Establishments,” at www.ci.nyc.ny.us/html/nypd/downloads/pdf/crime_prevention/Best_Practices_For_Nightlife_Establishments.pdf.

Editor’s Note on The Sociable City: Nightclub & Bar Magazine readers wanting to join a growing network of stakeholders from industry, government and community organizations dedicated to a safe and vibrant nighttime economy can join the Sociable City Network and access online resources, free webinars and peer to peer forums. You will also receive a free registration for a statewide nightlife forum in June 2010 being held in Pennsylvania, Colorado, Florida, North Carolina or California (and more in the fall) (http://rhievents.org/forum) with your membership. Go to www.SociableCity.org and join using discount code - nightclub&bar - on the payment form to save $25.